What Changed to Make Edwin Diaz So Dominant This Year?

Getting ahead early in counts and an increase in slider usage have Edwin Diaz looking like one of the best closers in baseball again.

When the New York Mets traded for Edwin Diaz prior to the 2019 season, they felt like they were acquiring best closer in baseball. Then just 24 years old, Diaz was coming off a season in Seattle where he pitched to a 1.96 ERA with 124 strikeouts in 73.1 innings. Diaz led the MLB with 57 saves.

The Mets acquired the flamethrower with four years of team control, as he was clearly the most valuable piece in a trade that saw Robinson Cano come back to New York and top prospects Jarred Kelenic and Justin Dunn head to Seattle.

Unfortunately for the Mets and Diaz, the first three years of his tenure in New York were rather underwhelming. First in 2019, Diaz endured the worst season of his career, getting tagged with 15 home runs in the juiced ball season, leading to a career-high 5.59 ERA and seven blown saves.

Diaz was elite again in 2020, pitching to a 1.75 ERA with 50 strikeouts in 25.2 innings, but all that took place in a COVID season that still doesn’t even feel real. Last year he was solid, pitching to a 3.45 ERA. But still, as we compare Diaz’s first three seasons in Queens to his first three in Seattle, it is clear the Mets haven’t quiet gotten what they expected from their closer.

| Edwin Diaz’s Career Stats | Games | ERA | WHIP | SV | SVO | K/9 | FIP |

| Seattle Mariners (2016-2018) | 188 | 2.64 | 1.02 | 109 | 121 | 14.2 | 2.56 |

| New York Mets (2019-2021) | 155 | 3.23 | 1.22 | 64 | 81 | 14.6 | 3.22 |

Now in his final year before hitting free agency, Diaz is looking every bit as elite as he was in Seattle, if not better. A few key adjustments have led to Diaz getting the most out of his always elite stuff, giving the Mets the lockdown closer they wanted all along.

What is Diaz Doing Differently in 2022?

On the latest episode of Locked On Mets, I explored what we have seen from Edwin Diaz this year compared to year’s past. Through my research there were two things that jumped out on Diaz. He is getting ahead early in counts more than ever before and he’s now throwing his slider more than his fastball.

Diaz has always had an elite two-pitch mix, with a fastball that touches 101 and a tight slider that averages 90.1 MPH but can touch 95. Simply put, if Edwin Diaz is commanding his stuff and sequencing it properly, he is untouchable.

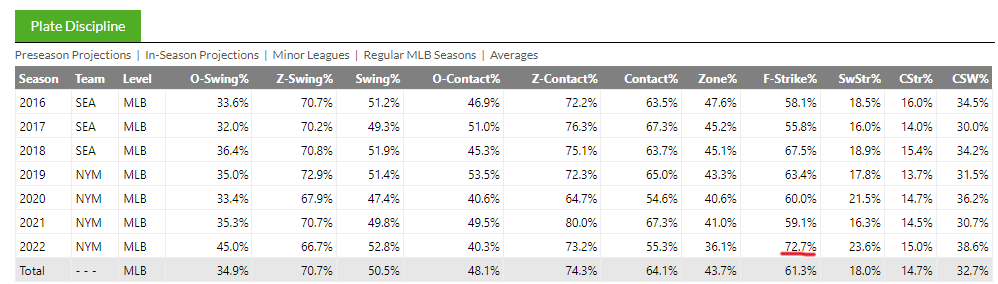

Looking over Diaz’s Fangraphs page, there was one number that popped when looking at a breakdown of batter’s plate discipline against him this season.

Check out his first strike percentage (F-Strike%) compared to year’s past.

Now this is still a small sample size compared to a full season, but Diaz is currently getting a first-pitch strike over 70% of the time. Over a full 162-game season, that number could come down, but if we compare his 72.7% F-Strike% in 15 innings this season to his 60% F-Strike% in 25.2 innings pitched in 2020, we can see that there is real intention here to get ahead early.

By pounding the zone early in counts, Diaz is then able to do the exact opposite for the rest of the at-bat. He’s basically saying, “Here’s my 100 MPH fastball, or a slider over the dish to start an at-bat. If you don’t hit that I’m ahead 0-1, now I will just bury five sliders and dare you not to swing at two of them.”

Sometimes batters like to take the first pitch and Diaz is just taking advantage of that by challenging them. There could be a correction at some point this season where batters try to ambush Diaz early, but his stuff is so good that he will easily be able to counter that.

Diaz’s Zone% this season is a career-low 36.1%, meaning he is throwing pitches in the strike zone less than 40% of the time for the first time in his career. Yet his 49.1% strikeout rate would be the best mark of his career. This is because he is letting the batter get themselves out.

Once Diaz gets ahead, he can work around the edges and get swings and misses to get his strikeouts. Batters are swinging at pitches outside of the zone (O-Swing%) 45% of the time against Diaz this year. That is about 10% better than his career average.

It is a lot harder to spit on Diaz’s nasty slider when you are behind in the count. This season, Diaz is getting whiffs on 55.3% of swings against the pitch as hitters in swing mode have to be geared up for his upper triple digits fastball as well. There is no doubt that his slider is his best pitch and he is finally leaning into how well the offering tunnels with his fastball.

For his career, the most he has ever thrown his slider is about 38% of the time in each of his last two seasons. This year, Diaz is throwing his slider with 52.8% of his pitches.

It might not sound like much, but going from essentially 60-40 fastball to slider usage to now being closer to 50-50 unlocks everything for Diaz. As tempting as it is to throw the 101 mph heater when you have it in your back-pocket, Diaz does batters a favor when he throws them a fastball.

Batters are hitting .250 with a .625 slugging percentage on his fastball this season. Now that’s inflated cause he has given up two home runs out of 12 batted ball events on the pitch, but it still shows that MLB hitters don’t have as much difficulty turning around 100 mph, as they do barreling up a late-breaking slider that comes in at 91 mph. Hitters are just batting .088 with a .133 xSLG on his slider.

Diaz’s last save against his former team is a perfect example of how dominant he can be with this new approach. Saturday night, Diaz entered one-run game and had to face 3-4-5 in the Mariners order.

Each of his eventual strikeout victims saw a first-pitch slider get called for a strike. J.P. Crawford was first. He got a pitch to hit 0-1, a 98.9 MPH fastball that Diaz dared him to hit. Then he got two sliders out of the zone. First one he spit on, second one he struck out swinging.

Eugenio Suarez was next and Diaz must have been licking his chops considering he strikes out in over 30% of his plate appearances. First pitch slider called for a strike, then two sliders nowhere near the zone. Suarez didn’t take the bat of his shoulder and was sitting 2-1. Diaz hit him with 98.7 up in the zone and Suarez couldn’t catch up.

Now ahead 2-2, Diaz buried two more sliders and finally got Suarez to bite on the last one for his second-straight punchout. Jesse Winker made for the trifecta, but he was the toughest customer.

Winker worked an eight-pitch at-bat by getting a piece of four different sliders. Diaz had enough, so he put him away with a 100.5 MPH fastball that was tipped into catcher Patrick Mazeika’s glove for the final out.

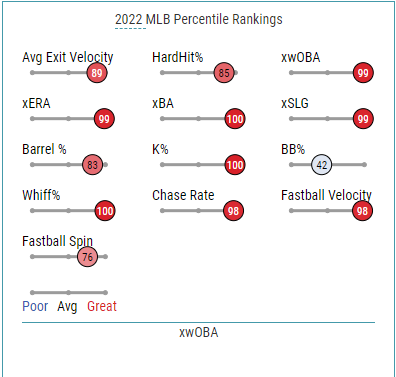

Diaz has produced some eye-popping numbers through his first 15 innings. If he can replicate this sample three times over, the 28-year-old is going to get paid a lot of money in free agency.

His left on-base percentage is at 100% right now and he has a career-best K-BB% of 40%. Expected metrics tell us that his 1.80 ERA is actually inflated, as his xERA is 1.36. Diaz’s Baseball Savant page is filled with bright red, showing his top-tier dominance in a league filled with great pitching.

Diaz has faced 55 batters this year. Seven of them have gotten hits. Five of them of drawn walks. Sixteen of them have hit into outs. The other 27 have been punched out. Diaz has always had the ceiling of being the best closer in baseball. If he keeps this up all season, that is a title he can certainly regain before he tests the open market this offseason.

When the Mariners and Mets originally made the trade to send Edwin Diaz to New York, he was probably the third-most talked about piece to that deal. Many laughed at the Mets for taking on Robinson Cano’s remaining five years and over $100 million (still a terrible decision), especially since they gave up a consensus top 100 prospect in Jarred Kelenic.

Now in the fourth season since that trade, Cano is a Padre, Kelenic is back in Triple-A after a rough start to his sophomore season and Diaz is the star closer on a first place team. Go figure.