The Hall of Fame Case for Billy Wagner

Wagner is in his final year on the National Baseball Hall of Fame ballot. Should he get a last-minute invitation to Cooperstown?

Billy Wagner is approaching the peak in his climb up Everest.

His steady climb to 75% of votes on the BBWAA Hall of Fame ballot, though it has taken its time, will culminate with this year’s results, likely leading to his induction into baseball’s most exclusive club.

Wagner’s path to this point has been like few others’. After hanging around 10% of the vote for each of his first three years on the ballot, he steadily found his way up to 73.8% in 2024, just five votes shy of induction. In that time, Wagner jumped up an additional 15% of the vote in three different years.

As time has gone by, it seems like less of a surprise why Wagner’s case has become so appealing. The evaluation of many Hall of Fame cases has evolved over the 10 years Wagner has spent awaiting his induction.

These changes cater to Wagner’s strengths. His 187 career ERA+ and 33.2% strikeout rate over 903 innings pitched make his case look a lot more clear-cut than it might have seemed in 2016.

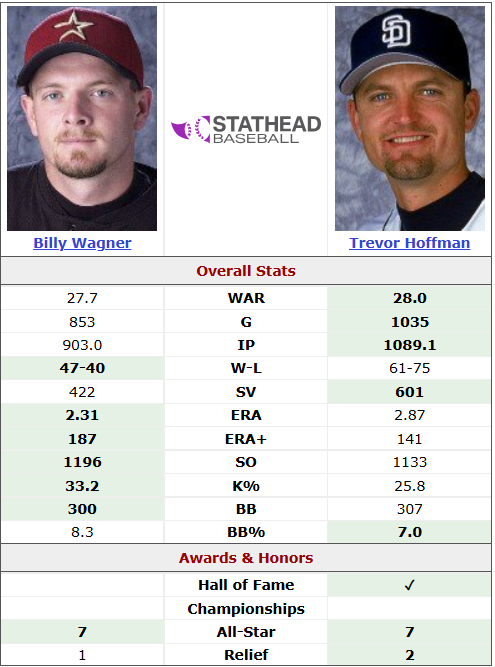

Wagner has seen two other relievers elected by the BBWAA during his time on the ballot: Trevor Hoffman in 2018 and Mariano Rivera the following year. Although his career might not stack up with Mo’s, he and Hoffman could be looked at through a similar lens:

The one advantage Hoffman holds over Wagner is in saves. 600 was his magic number. He was the first closer to reach 600 career saves. He would retire as the all-time saves leader, though he was later surpassed by Rivera.

This was what defined Hoffman’s career when he appeared on the ballot. When people thought of Trevor Hoffman, they thought of three outs to lock down the ninth inning to preserve a close win. And why not? After all, he had done that more than anyone when he called it a career.

Saves, at one point, were the defining stat for relief pitchers. Being the all-time saves leader as a closer was viewed like being the home run leader as a hitter or the wins leader as a pitcher.

Wagner was never atop this leaderboard. In fact, he was never close. Although Wagner ranked fifth all-time in saves at the end of his career and ranks eighth all-time today, there’s still a mountainous gap between him and the top of the leaderboard.

The difference between 601 saves and 422 saves was the difference between Hoffman being inducted in his third year and Wagner failing to rise above 10% on his first three ballots.

Hoffman appeared in 182 more games than Wagner. It’s natural that he would have more saves. Where Wagner does hold the advantage over Hoffman, however, is basically everywhere else.

Although it came in a smaller number of innings, Wagner has a clear edge in run prevention. A 2.31 career ERA and 187 ERA+ skyrockets him past Hoffman.

In 186.1 more innings, Hoffman gave up 115 more earned runs. That’s the equivalent of a 5.56 ERA. So, while the extra innings might have made Hoffman appear to be the more appealing candidate, Wagner was more effective on the mound.

Wagner also tallied more career strikeouts than Hoffman despite the innings gap. Over the later years of Wagner’s time on the ballot, voters have begun to look more closely at his strengths: a low ERA and high strikeout rate. With a deeper glance, those numbers should pave a clear path to the Hall of Fame.

Wagner’s Run Prevention

A 2.31 ERA, good for a 187 ERA+. This coming in over 900 innings of work across 16 MLB seasons.

Only 21 pitchers throughout baseball history have tossed over 800 career innings and posted a career ERA below 2.35. This list includes Hall of Famers like Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth and many other pitchers who thrived in baseball’s “deadball” era.

In fact, Ruth, who played his last MLB game with the Boston Braves in 1935 (and threw his last pitch for the Yankees in 1933), was the third most recent pitcher on this list to suit up for a major league team.

Before the 1930s, leaguewide offense was at one of the lowest points the game has ever seen. In other words, these pitchers were putting up ERAs below 2.35 when the league-wide ERA was around the mid-to-high twos.

Wagner, however, played and even peaked at the height of the steroid era, the golden age of offense since the game integrated. He was putting up these numbers at perhaps the most difficult time to be a pitcher in the major leagues. This is where ERA+ comes in.

Billy Wagner is one of the greatest preventers of runs the game has ever seen when adjusting a pitcher’s results to the era they pitched in. His 187 ERA+ ranks 2nd all-time among every pitcher to throw at least 400 career innings. Only Rivera stands above him in this category.

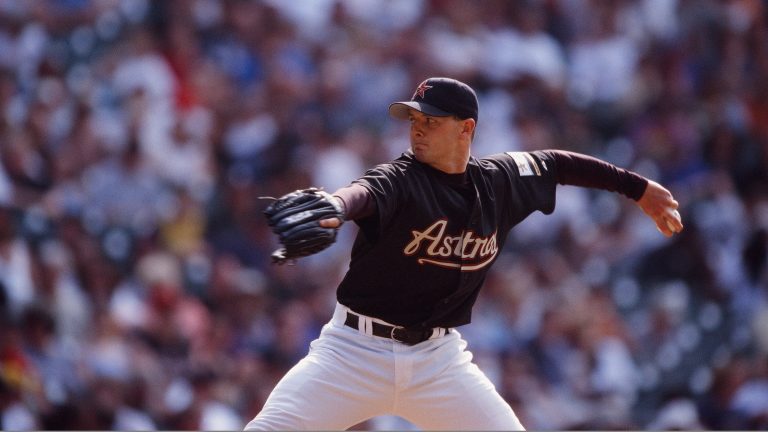

This was who Wagner was from the beginning to the end. In his first full season at age 24, he pitched to a 2.44 ERA in 51.2 innings with the Astros, good for a 159 ERA+. He finished his career with a 1.73 ERA across 69.1 innings with the Braves in 2010, earning a 275 ERA+.

To this day, Wagner’s closing act remains the lowest ERA a pitcher has ever posted in the last season of his career, minimum 50 innings pitched.

This was familiar territory for Wagner. In 14 of his 15 proper seasons, he finished with an ERA below three. In 13 of those years, he did so in at least 45 innings of work. He remains one of nine pitchers of all time to have at least 13 such seasons.

Six of the other pitchers to do so are in the Hall of Fame, with Clayton Kershaw representing one of the non-HOFers.

Adjusting for era, Wagner also had 13 seasons with an ERA+ above 140 in at least 45 innings pitched, meaning he was at least 40% better than the average pitcher in run prevention. The other two pitchers to have at least 13 such seasons are Hall of Famers: Rivera and Hoyt Wilhelm.

But at his peak, a 140 ERA+ was nothing for Wagner. On four different occasions, he logged an ERA+ above 240 (min. 45 IP). That’s twice the run prevention skills of the average pitcher and then some. He is also one of just three pitchers to do this in four separate seasons of at least 45 innings. The other two? Rivera and Joe Nathan.

For nearly all of his career, hitters had immense trouble scoring off Billy Wagner. Statistically, they had just about as much trouble as anyone has ever had against a pitcher with his workload. After all, it’s hard to score off someone hitters struggled to even make contact against.

A Swing-and-Miss Legend

It’s not just the fact that Wagner could get batters out at an efficient rate, it’s the dominance he did it with.

In 903 innings, Wagner retired 1,196 batters on strikes. Nearly one-third of all plate appearances against him ended on strike three. In fact, Mariano Rivera, the greatest reliever of all time, could walk back on the mound, face exactly 782 batters and strike them all out. It still wouldn’t be enough to top Wagner’s 33.2% strikeout rate.

Strikeout rates began rising around Wagner’s debut, but this was still unheard of in the 1990s and 2000s. Fangraphs K%+ adjusts a player’s strikeout rate to compare it to the era in which they pitched. A K%+ of 100 is equal to league average, similar to ERA+.

Among all pitchers with over 500 career innings, Wagner’s 190 K%+ ranks second all-time, falling short to just Hall of Famer Dazzy Vance.

In all but two of Wagner’s seasons, he struck out at least 10 batters per nine innings. His 13 seasons with 10 or more K/9 in at least 45 innings pitched make him one of three pitchers to have as many such seasons. He trails only Randy Johnson and is tied with Max Scherzer.

He is also one of just five pitchers to have at least five seasons with 11 or more K/9. Joining him on this list are Johnson, Aroldis Chapman, Kenley Jansen, and Craig Kimbrel. He is the only reliever of his era or prior to have nine or more such seasons.

Overall, Wagner had 13 seasons with a 140 ERA+ or higher and at least 10 K/9 with a workload surpassing 45 innings. No one else in baseball history logged more than nine such seasons.

The consistency of his dominance in multiple aspects of pitching is one of a kind and is still something we have never seen replicated.

A Relief Trendsetter

In many ways, Wagner was the predecessor to what we now know as the modern relief ace: A dominant force on the mound with high strikeout numbers and a low volume of hits. This brings to mind pitchers like Jansen, Kimbrel, Chapman, and maybe Josh Hader later down the line.

If and when those guys eventually appear on the Hall of Fame ballot, they could look at Billy Wagner as inspiration for their own cases, should Wagner earn induction.

The difference, of course, is that Wagner accomplished what he did 10-15 years before any of them. It’s no wonder why only eight relief pitchers, including some who were also starters for parts of their careers, have been elected to the Hall of Fame in its nearly 90 years of existence. Closing is a growing part of the game that didn’t exist in a meaningful capacity for much of baseball history.

Wagner was a symbol of the transition. While he doesn’t have the save totals of Hall of Fame relievers of his time like Rivera or Hoffman, he showed years in advance what today’s dominant reliever looked like.

By the way, his career numbers are better than today’s legacy relievers. In a larger workload, he towers 30 points above Jansen, Kimbrel and Chapman in ERA+, while being right there with them in strikeout rate.

If the BBWAA can’t see Wagner as a Hall of Famer, we might as well decide we will never see a Hall of Fame reliever for the rest of time.