The Hall of Fame Case for Gary Sheffield

Despite a long career and impressive resume, Gary Sheffield is still seeking a plaque in his final year on the BBWAA Hall of Fame ballot.

With a memorable batting stance and a penchant for ranking among the league leaders in several offensive categories throughout his 22-year career, few played harder and were more hard-nosed than Gary Sheffield.

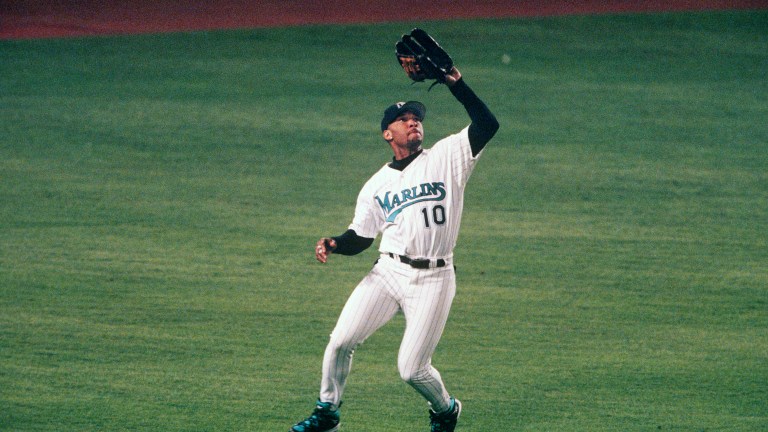

One of only 28 players to reach 500 home runs for their career, Sheffield was a hot commodity for clubs in search of one more run producer in the middle of the lineup. He played an instrumental role for the Florida Marlins in 1997, helping them win the first World Series in franchise history, and benefitted Atlanta and the New York Yankees on their way to the postseason every year between 2002 and ’06.

“There was quite a long period of time when Gary Sheffield was the most feared right-handed hitter in baseball,” said manager Jim Leyland following the press conference in which the legendary skipper was announced as part of the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Class of 2024.

Fans of a more recent generation unfamiliar with Sheffield might examine the career numbers of Miguel Cabrera and find similarities between the two, particularly in terms of OPS and OPS+.

Sheffield was traded five times, twice for future Hall of Famers, and brought his baggage and several controversies to each of the eight clubs for which he played.

Now, Sheffield sits at a crossroads despite a strong resumé. This is his 10th and final year in front of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Though his support has grown dramatically, rising from 11.1%-13.6% throughout his first five years on the ballot up to 55.0% last year in his ninth go-round, it will still take a notable bump for Sheffield to hear his name during Tuesday’s official announcement.

The Argument Supporting

Gary Sheffield’s illustrious baseball career began early in Tampa, FL. Eight years before making his big league debut, he starred as an 11-year-old with the Belmont Heights Little League where his team lost the Little League World Series Championship Game to Taiwan.

The nephew of Dwight Gooden, Sheffield began his MLB journey as a 19-year-old shortstop with the American League’s Milwaukee Brewers during the late 1980s and eventually finished in 2009 as a left fielder for the New York Mets.

Over the course of two decades in the majors, Sheffield demonstrated outstanding offensive prowess, amassing impressive numbers that support his Cooperstown candidacy. His counting statistics place him among the game’s most elite sluggers of all time: 509 home runs, 2,689 hits, and 1,676 RBI. Toss in 253 stolen bases — 108 of which came after he turned 30 — and his unique blend of power and speed puts him alongside Willie Mays, Barry Bonds and Alex Rodriguez as the only players to reach the 500 homer and 250 stolen base club.

A nine-time All-Star, Sheffield added five Silver Slugger Awards to his trophy case. He won a batting title in 1992 with the San Diego Padres, becoming the only batting champ in their franchise history not named Tony Gwynn.

The same year, Sheffield nearly won the first Triple Crown in the NL in 55 years; with 33 home runs and 100 RBI, he fell short by two home runs and nine runs batted in. He finished third in Most Valuable Player voting that season. Over the next 14 seasons, he would be mentioned on seven different MVP ballots, finishing as the runner-up in 2005 with the Yankees.

Beyond the individual statistics, Sheffield’s impact extended to each of his teams in the win column. He was part of the first Florida Marlins World Series-winning team in 1997, batting third in all seven games and posting a .947 OPS to go along with five runs batted in during the Fall Classic.

Sheffield earned a reputation as a middle-of-the-order bat, making a staggering $168 million for his services. Along the way, he chipped in with 509 home runs. Of the 28 players to reach the 500 mark, 19 are already enshrined in Cooperstown. Two more, Albert Pujols and Cabrera, have yet to appear on a ballot, while the remaining seven starred during the home run renaissance of the 90s. We’ll get to why Sheffield is among the seven men out in just a moment…

In his final season before hanging up his cleats, Sheffield added another exclusive club to his resume when he hit 10 home runs with the New York Mets at the age of 40. The list of players who homered as a teenager and as a 40-year-old counts just four: Ty Cobb, Rusty Staub, Rodríguez and Sheffield.

Few were as consistent as Sheffield during the 90s and 2000s. He achieved 2.7 offensive Wins Above Replacement (per Baseball Reference) 16 times, a feat surpassed by only 15 players all-time. He also reached 100 RBI in eight different seasons, a total tying him for 30th-most in a career.

During his best 10-year stretch from 1996-2005, Sheffield had the third-best OPS+ (154) of any player with at least 1,000 games played, topped only by Barry Bonds (210) and Manny Ramírez (160).

According to JAWS, a metric created by Jay Jaffe to evaluate players from baseball’s many different eras, Sheffield is the 24th greatest right fielder of all time. Considering there are 27 right fielders in the Hall, the most of any position, and that Sheff is ranked ahead of 12 of those players, it’s impossible to deny that the man has Cooperstown credentials.

When using a tool like Bill James’ Similarity Scores, which makes player comparisons based on career and individual season statistics, the argument becomes even more compelling. Sheffield’s top 10 most similar players include nine Hall of Famers, plus Carlos Beltrán, who has received significant support in his second year on the ballot.

Adrián Beltré, well on his way to becoming a first-ballot Hall of Famer, has seven of Cooperstown’s finest in his top 10, although the three others — Rafael Palmeiro, Beltrán and Cabrera — possess more than sufficient Hall of Fame credentials of their own.

The Argument Against

Sheffield is not the perfect candidate. He’s not former teammate Mariano Rivera, who was elected on 100% of ballots in 2019, nor is he a no-doubt, squeaky-clean candidate like Beltré. The reasons why he has not reached 75% during his first nine years on the ballot are plentiful.

In an age when the person you are away from the field is weighed almost as heavily as the player you were on it, Sheffield had a complicated career. There were arrests, controversial statements and general moments of questionable behavior. Surprisingly, this hasn’t been the sole focus of those voters who leave his name unchecked on their Hall of Fame ballot.

Sheffield also played during an era when performance-enhancing drugs were more accepted. It increased excitement and increased revenue for players and, much more so, for owners. Even after the embarrassment the sport faced following the Steroid Era, the commissioner at the time, Bud Selig, was given a place in the hallowed Hall as if nothing disgraceful happened at all.

In the early 2000s, ties to BALCO and Barry Bonds’ trainer surfaced, putting the first major blemish on Sheffield’s record. Soon after came the Mitchell Report, which disclosed the results of an investigation on the use of PEDs. Though the findings were purely allegations about the 89 players named in the report, Sheffield was among those held guilty in the public court of law.

Another knock on Sheffield pertains to having played for eight different teams. Because of this, doubts about his impact as a franchise player have been raised. Some argue that despite his individual accomplishments, his transient nature diminishes his value compared to players who spent the majority of their careers with fewer teams.

That said, others in Cooperstown have appeared with at least seven franchises. Sheffield would be the 14th such player – the first since closer Lee Smith was enshrined in 2019 – but the only one to be an All-Star with five different clubs.

Defensively, the metrics rate Sheffield as one of the worst to ever field a position. He’s the second-worst position player in the history of the game according to Baseball Reference’s defensive WAR, behind only Adam Dunn. (It should be noted that six of the next nine behind Sheffield are either Hall of Famers or soon-to-be Hall of Famers.) Using Rfield (WAR Runs Fielding), only Derek Jeter is worse.

Yet, were Sheffield deemed absolutely unfit to play the outfield by his managers or hadn’t spent more than half his career in the National League without the option to be a designated hitter, he wouldn’t have had to play the field and could have gone down as the greatest DH of all time.

The Baseball Hall of Fame lists only three players at DH: Harold Baines, Edgar Martínez and David Ortiz. By offensive WAR, Sheffield ranks 37th all-time with 80.7 oWAR, well ahead of the 66.9 oWAR of Martínez, the highest of the trio. Even if you wanted to include first baseman Frank Thomas in that group because the majority of his games came at designated hitter, Sheff would still slot ahead of Big Hurt’s 80.4 oWAR.

Final Evaluation

A little more than a decade ago when the massive green expanse that makes up the lawn at the Clark Sports Center was filled with fanatics excited to see the living Hall of Famers in attendance and listen to speeches by the newest members in the Class of 2011, there weren’t many in the crowd wearing Roberto Alomar jerseys.

Some wore his No. 12 Toronto Blue Jays jersey thanks to a contingent from Canada making the seven-hour drive to celebrate the team’s consecutive World Series wins in 1992 and ’93, as the general manager of those clubs, Pat Gillick, was also being enshrined.

Alomar, who played with seven teams, spent only five seasons with the Jays. Every other stop was three years or less. He wasn’t Craig Biggio, a contemporary who also debuted in 1988 and spent 20 years with one franchise, but he was a Hall of Fame second baseman nevertheless.

Should voters really be concerned that the longest Gary Sheffield stayed with one team was six years with the Marlins? Will the double standard of the Steroid Era take a step in the right direction? Will Sheffield receive a substantial boost of 20% support to reach the 75% mark and become the sixth Hall of Famer who debuted in 1988?

Even if the answer is “no” to all of the above, Sheffield’s candidacy will continue to be discussed. His next route to reaching upstate New York would come in Dec. 2025 via the Contemporary Era Committee, the same one that recently elected his two-time manager Leyland.